At some point in your life, you’ve probably been on a team.

Whether it was a baseball team when you were growing up, a team of volunteers working to clean up a local community, or a marketing team working to support your sales department — it’s likely that you’ve experienced the feeling of strength in numbers. After all, everyone always says that the sum of a team is greater than any individual, right?

From locker room speeches to motivational seminars, the concept of team empowerment is constantly being reiterated and reinforced.

But why? Why do we value teamwork so much? And how is it influencing employee performance in your office?

The Truth About Teams

What sparked me to write about teamwork is the high expectation I hold for myself and for how other teams should perform. I’m an optimist by trade, which means I believe that if teams are motivated and willing to sacrifice anything to win, then the outcome should be nothing less than perfect, right?

Truth be told, this expectation only sometimes comes true. In fact, I’ve noticed that time and time again, teams underperform despite the level of talent and leadership they possess. And when I ask people if they prefer working in groups or as individuals, they often say, “by myself.”

This got me thinking: Why is this response so common if teams are thought of with such high regard?

The reason — The Ringelmann Effect

What’s the Ringelmann Effect?

In 1913, a French professor named Max Ringelmann discovered something quite astonishing about teams. His findings illuminate why most people prefer working as individuals than in groups.

Ringelmann found that as groups form, individuals slack. This phenomenon is known as the “Ringelmann Effect.”

Simply put, as team size increases, individual performance and productivity decreases. This notion was made famous by his rope pulling experiment. Think about it this way: Your boss asks you to participate in a game of one-on-one tug of war. You slug some water, blow on your palms, grasp the rope, and grit your teeth as you relentlessly pull on the 30 foot rope. As the flag inches closer and closer to your side, a bead of sweat drops off your nose and the referee blows the whistle indicating you have won. You did it. You made your boss proud.

You won because of three reasons: The outcome was 100% in your control, you could not hide in the identity of the team, and no one else is there to pull the rope but you.

Now your boss decides to test their luck by putting a little more at stake. Your marketing department is matched against the sales team in a winner-take-all, eight vs. eight battle of the rope. Again you bend over, grip the rope, and pull. This time there’s no grinding of any teeth, no beads of sweat, and no winning — the flag crosses the sales side, and you’re left sulking.

How could this be? They had you on the team, right?

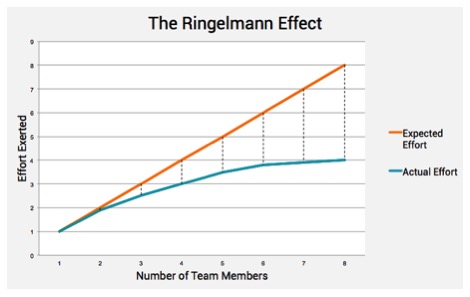

Ringelmann found that with one person pulling on the rope, they gave maximum effort. As more people pulled on the rope, each individual gave less effort. Sadly, when an eighth person was added to the team, members pulled half as much as their maximum potential strength. This graph indicates Ringelmann’s data:

As the group gets larger, the amount of work per person decreases from its maximum of 1.

Source: Ringelmann (1913)

These findings can be applied to any office. As business teams form, individuals tend to feel less responsible for the overall output leading to reduced individual effort. Members take on the mentality of, “If I don’t pull as hard on the rope, no one will really notice, right?”

I know there are a few things you must be thinking right now …

“I hope this isn’t happening in my teams! I better do something about it before it gets worse, and quick!” or “There is no way this is happening in my office. Everyone is always giving 100% effort. I’m sure of it.”

Well, to the first person I say, hold up. Before you start slicing and dicing up your teams, take a breather. To the second person, you’re wrong. This is most likely occurring — you just don’t know it yet.

So before you begin accusing people of being slackers (I never suggest you do that), let’s discuss the necessary steps to avoid the infamous Ringelmann Effect.

How to Avoid the Ringelmann Effect

As a manager, make sure one large pizza is the perfect amount of food to feed your team. A large pizza should feed three to four people comfortably — and a three to four person team is the ideal size for gaining the most out of your team.

Can’t reduce the size of your team?

It’s okay. You’re not alone. And you can still avoid the Ringelmann Effect by making note of these three helpful secrets.

Skip the All-Star Team

Research suggests that people work harder if they expect others in the group to work poorly. If everyone is an all-star, people hold the expectation that other members will pull the bulk of the work, producing low individual effort.

Think about the 2004 Boston Red Sox. They surely weren’t the best team on paper (only two players made the all-star team and one of them was a pitcher who only played every 4-5 games), and no one expected them to win the World Series that year. So how did they break the 85-year-old curse and avoid the Ringelmann Effect?

When each player stepped into the batters box, or took the field, they did not expect anyone else to pull the weight of the team except themselves. Simply because very few were “all-stars” — they saw their role as an integral part of the team that had a significant impact on how well the group performed

It’s human nature to want to assemble the best team available. We want only all-stars on our side. However, watch out for this tactic. In some cases, having only all-stars allows for members to believe that if they don’t perform well, others will pick up their slack.

Be Cognizant of Group Identity

In large teams, it’s hard to identify who is contributing to what. The larger the team, the larger the project becomes. The larger the project, the less likely individuals will be noticed for their work. As groups get larger, individual identities disappear and shift from multiple singular identities to one large group identity.

You’re probably thinking, “Isn’t this good? Don’t you want strong group identity?”

Yes, while you’re right from a team cohesion standpoint, your thought process seems a bit off from a motivation standpoint. Here’s why: As individual identities dissipate, people often begin to feel anonymous. Therefore, if members slack, the “slacker” identity gets put on the group and not the individual.

Make Work Identifiable

Seinfeld’s George Costanza put it best: “Yes. Yes. Everybody has to like me. I must be liked!”

It’s undeniable that people are concerned with how others evaluate them (known as evaluation apprehension). Lucky for managers, when team members are concerned with their evaluation, they exert more effort. This can be done by making more tasks identifiable.

Identifiable tasks often result in members pulling harder on the rope, otherwise known as exerting greater effort toward the overall group task. Due to the identifiable nature of this task, members become increasingly concerned with how well they’ll be evaluated.

To facilitate this, slice your teams work into manageable bite size bits that each team member is accountable for. By doing this, it’s likely that you’ll be able to identify and correct the slackers quickly and easily. Just like the rope pulling situation if their not identifiable for their work, less output occurs.

Getting Started

Managing teams is tough — there is no doubt about that.

No matter how hard we try to control all the seemingly controllable variables, there will always be another one showing up. This post is not meant to solve every management hiccup in your office — rather it’s designed to make you aware for how your team members interact with each other so you can stop the Ringelmann Effect before it runs rampant in your office.

Have you experienced the Ringelmann Effect in your office? What are your favorite tips for optimizing your team?

![]()